Lima–Trujillo–Cajamarca–Chiclayo–Piura–Mancora–Punta Sal–Tumbes–Cuenca (Ecuador)

After celebrating the New Year of 2006 in Lima, we embarked on a journey along the northern coast of Peru. Our plans also included crossing the border to visit one of the most beautiful cities in neighboring Ecuador—Cuenca.

As you travel along the coast (costa) on the Pan-American Highway, you’re mostly surrounded by lifeless landscapes. Stretching over many kilometers, the sandy-rocky dunes and hills sometimes resemble the paws of giant ancient reptiles. Sparse vegetation appears occasionally. The bare branches and sun-scorched trunks of small trees only highlight the harshness of the hot, arid climate. It felt strange to realize that we were traveling along the coast of a vast ocean, yet its water was not the life-giving moisture that nurtures lush vegetation on the land.

The riverbeds along the northern coast of Peru are mostly dry during this time of year. In January, it’s summer here, with temperatures reaching up to 40 degrees Celsius in some places. Nonetheless, the valleys with dry riverbeds offer some relief to travelers with their wild, natural vegetation. The water likely sinks deep underground, still providing some nourishment to the sparse local flora. There’s no rain at this time of year. Small fishing villages along the way often present a rather bleak picture. Houses made of earth, sand, and dried grass are considered a luxury. More often, we saw huts woven from dried palm leaves or reeds without windows, with a fabric-covered doorway. The closer the hut is to the ocean, the more sand the wind brings, forcing the inhabitants to constantly battle this natural phenomenon. The residents of such settlements are likely among the poorest segments of the local population, with fishing being their main occupation. We also passed through small towns that are more like villages in Russian terms. They were small and poor. The larger cities along the coast are like oases in the desert. Life begins with agricultural plantations of maize (corn), potatoes, or banana palms. The cities themselves are usually well-landscaped, with plenty of palm trees, olive trees, cacti, and other vividly blooming trees and shrubs.

Trujillo

Our first oasis on this journey was the city of Trujillo, located in the La Libertad department. The history of settlers in this department goes back more than 12,000 years. Cultures such as Cupisnique, Salinar, Virú, Chimú, and Moche were formed here. The Moche culture (3rd–7th centuries AD) became famous for its realistic ceramic works and so-called «pyramidal temples.» These constructions demonstrate the vast architectural knowledge possessed by this people. Later, the Chimú culture (12th–15th centuries AD) emerged here with its capital, Chan Chan—the largest ancient city in Latin America built from clay. In addition to architecture, this culture left behind magnificent gold jewelry and a complex irrigation system—aqueducts. In the 15th century, after fierce resistance, the Incas eventually conquered this kingdom. In 1534, with the arrival of the Spanish in the valley, the city of Trujillo was founded, becoming one of the kingdom’s main cities. Today, it is one of the economic and cultural centers of northern Peru, known for its beautiful dance «Marinera,» stunning beaches, and traditional «caballitos de totora» boats.

Once a favored resting spot for the Spanish on the route from Lima to Quito, this beautiful coastal city was titled the «most luxurious city.» Today, traces of the colonial era remain in the decorative window grilles and wooden balconies designed so that high-society women could look out onto the street while remaining unseen. Later, this city gained fame as the first city in northern Peru to declare independence from Spain, on December 29, 1820. Initially, this fact seemed a bit amusing to us, given that the founding of the city is linked to the arrival of the Spanish. However, we later understood that it was primarily the descendants of Spanish settlers who had enriched themselves through exploiting the indigenous people that sought to declare independence from Spain. They did not want to pay taxes to the Spanish crown.

The modern post-Christmas Trujillo greeted us with numerous decorated Christmas trees in the city’s central square. Many were entirely artificial constructions, yet the creators’ imagination was impressive. At the center of the large monument stood the traditional nativity scene depicting the birth of baby Jesus. By evening, the square was aglow with colorful lights. Clowns, mime artists, painters, photographers with amusingly dressed llamas, and locals with children of all ages filled the square. A festive atmosphere prevailed.

The following days were dedicated to exploring the ancient cultures of Chimú (12th–15th centuries AD) and Moche (3rd–7th centuries AD)—the mysterious people named after the Moche River in northern Peru, with their settlements, cult structures, painted pottery, and stunning ceramic figurines and vases created by these talented indigenous people.

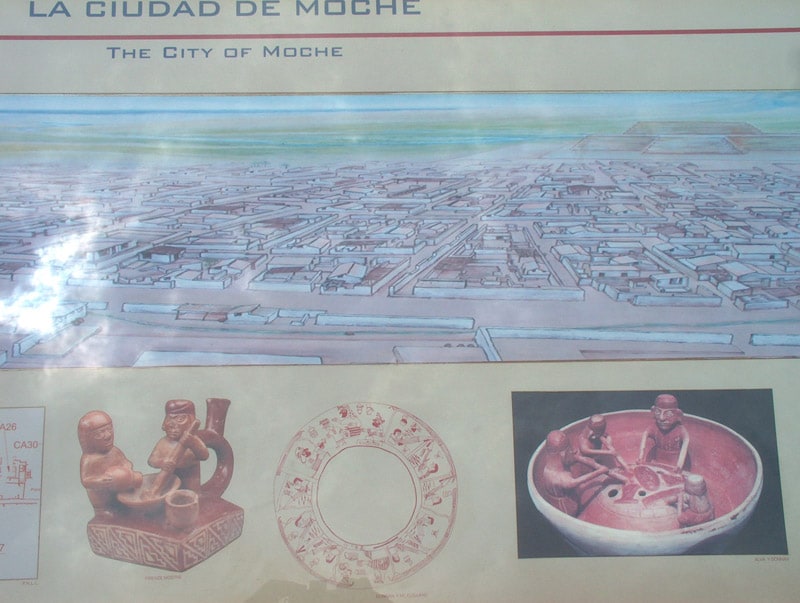

In the Moche Valley, 5 km from Trujillo lies the largest pre-Columbian city in the Americas, built from clay. Its name is Chan Chan. In the Moche dialect, it sounds like «Hank Hank,» meaning «Sun Sun.» On the coastal plains of Peru, stretching between the Andes and the Pacific Ocean, there are no significant stone quarries. The primary building material here has long been adobe—sun-dried clay bricks. In Chan Chan, we gazed upon the ruins of the ancient city entirely constructed from these bricks. Chan Chan was once the capital of the wealthy, powerful, and densely populated Chimú state.

At the entrance to the silent city of the Chimú people, we encountered a very unusual dog. This is an ancient breed known here as the Peruvian «el perro peruano.» It has no hair on its body and was originally a vegetarian. Unfortunately, in modern times, people began feeding these dogs meat, and since this breed was not adapted to such a diet, they started developing joint diseases due to metabolic disorders. This dog accompanied us the entire way as we strolled through Chan Chan. We discovered that it loved swimming. As we approached a pond that still exists in the ancient city, the dog could hardly contain its excitement, running back and forth, jumping, and squealing with delight. Its behavior puzzled us initially, but our Peruvian guide understood the dog well. He threw a stone into the pond, and the dog immediately leaped into the algae-covered water with great pleasure. This scene amused us greatly.

The city of Chan Chan spans an area of 18 km². From here, the rulers of Chimú governed their empire, which stretched almost 1,000 kilometers along the Pacific coast. The peak of their civilization is believed to have occurred in the 12th century, after the decline of the mighty Tiwanaku culture, whose center was located on the islands of the sacred Lake Titicaca. The Chimú people were highly skilled architects and engineers (they survived in these lands thanks to a sophisticated water supply system) and achieved great success in metalworking. There is reason to believe that the walls of the main buildings in the city were decorated with gold plates. Even today, one can appreciate the elegance and beauty of the ornaments carved into the clay bricks, although all the other valuable decorations of Chan Chan have long since disappeared.

A legend about the founding of Chan Chan tells of a man named Naymlap who came from the sea, established the city, and then returned to where the sun sets. Another legend states that a dragon lived in this city and created the Sun and Moon. But neither these nor other myths shed any light on the true history of the city’s origins. What can be said with certainty is that the Chimú people lived in a highly organized society. The rectangular layout of the city and its division into various districts suggest that logic and order were highly valued in this state. It appears that several thousand people lived in each of the walled city districts. The city center is formed by the Tsudi temple-fortress. The Hall of 24 Niches is particularly well preserved. Today, it is a rectangular courtyard enclosed by a wall with niches, in which one could sit. According to some hypotheses, the council of elders met here. The excellent acoustics allowed conversations to be conducted in whispers over a considerable distance—even today, this can be verified. According to another hypothesis, the niches held statues of gods. However, the purpose of many buildings in this city remains a mystery. The Hall of 24 Niches is part of a complex of buildings enclosed by a high protective wall. Within this complex, there are also ruins of huts, a water collection pool, administrative buildings, and platforms for religious ceremonies.

The Tsudi temple-fortress forms one of ten districts that made up the city of Chan Chan. Some of these districts were surrounded by high, nine-meter walls. Other city attractions include the Emerald Temple (Huaka Esmeralda) and the Rainbow Temple (Templo de Arco Iris), also known as the Dragon Temple (Huaka del Dragon). The Emerald Temple was excavated in 1923 and suffered significant damage from heavy rains two years later. This two-tiered pyramid-shaped structure is richly decorated with relief ornaments featuring marine flora and fauna. The Rainbow Temple is equally adorned with diverse and intricate designs.

When you observe both the geometric patterns of Chan Chan and the dragon-like, zoomorphic, and humanoid figures embellished with spirals, teeth, and triangles in the Dragon Temple, you can’t help but connect with the spirit of the Chimú people and their worldview. Today, Chan Chan stands as a frozen, incredibly strange desert city, evoking a sense of timelessness.

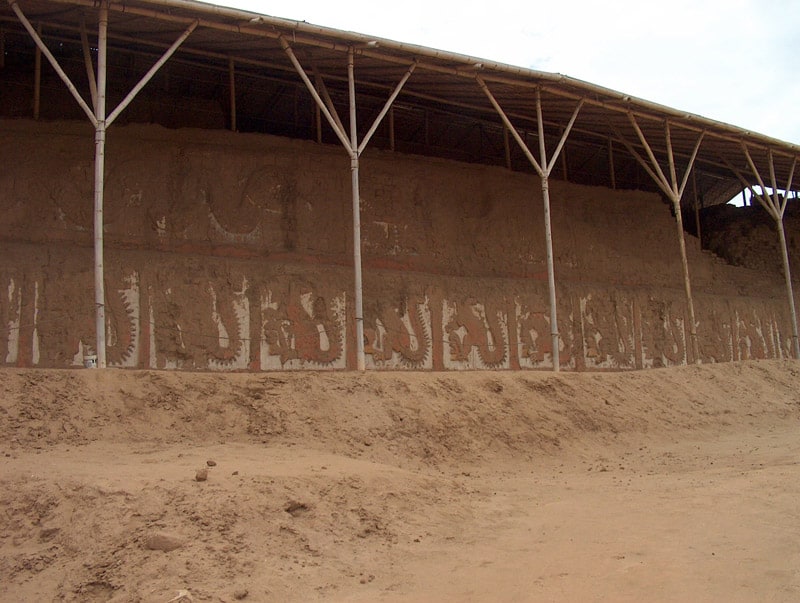

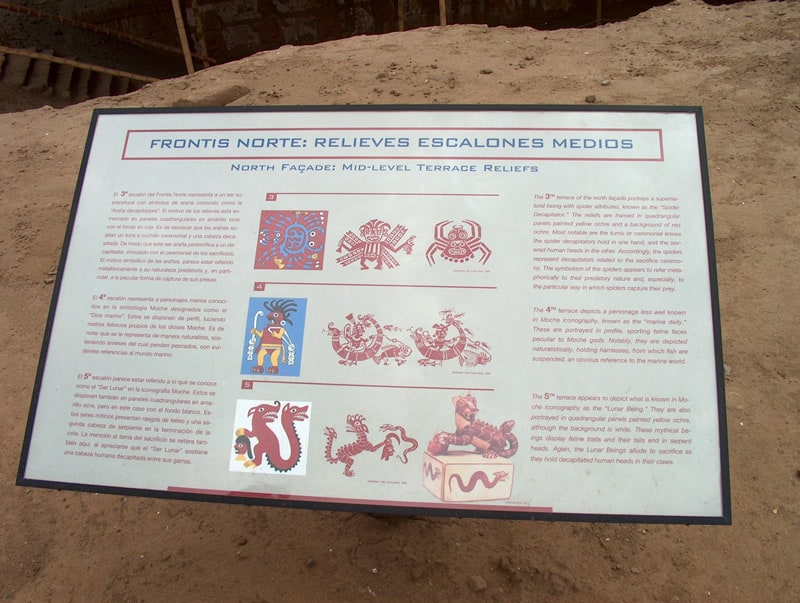

Traces of the even more ancient Moche culture can be found in the Moche Valley (8 km from Trujillo), where two surviving huacas (temples) are located: Huaca del Sol (Temple of the Sun) and Huaca de la Luna (Temple of the Moon). The system of constructing large structures, as well as the political and economic organization of their civilization, comparable to that of the Greeks, was inherited from the Gallinazo culture and later perfected in many aspects.

Today, scholars believe that the Moche people were the result of internal evolution in the Andean world. This assertion is based on studies of the region’s architecture and ceramics. It is believed that the Moche originated from three civilizations: the Chavín culture (1200–500 BC), from which the Moche inherited their main deities and architecture; the Salinar culture (500–200 BC), which introduced red and cream colors in ceramic production; and the Gallinazo culture (300 BC–200 AD). The Moche can be considered the first great ancient Peruvian civilization to create true cities and establish a defined state structure.

The Moche civilization flourished from the beginning of the Common Era until about 850 AD, with its peak from 300–600 AD. During this time, this population of around a million people engaged in hunting, fishing, various crafts, and irrigated agriculture, creating excellent irrigation systems. The Moche occupied a place in world history akin to that of the Greeks, utilizing all the achievements of earlier civilizations known to them.

It required power and immense wealth to erect the impressive Huaca del Sol and Huaca de la Luna. These cult and ritual monuments, built from adobe bricks, were once attributed to the Incas. The sensational aspect of their discovery was that these «pyramids» were not the work of the Incas but of the Moche. It was also revealed that between these «pyramids» (Huaca del Sol and Huaca de la Luna) lay a vast ancient city of the Moche civilization with a population of about 20,000 people.

But why are there only two of these «pyramids»? The Moche opposed two major deities—the daytime deity associated with the sun’s rays and the nighttime deity connected to the Milky Way and the Moon.

Unfortunately, time has not spared the architectural masterpieces of the Moche civilization. Today, a desert stretches between the two Huacas. From this area, one can see only the glowing lights of the Peruvian coastal city of Trujillo in the distance at night. The Huacas themselves, located near Mount Blanco, have been weathered over the centuries and ravaged by conquistadors in the 16th century, who sought to break apart the Huaca del Sol to access the gold hidden inside. Fortunately, they were not entirely successful. Notably, the Spanish who arrived here documented only the life of the Incas, unaware of the existence of the Moche. The rich civilization that preceded the Incas only began to attract researchers and scholars in the 1900s, when German archaeologists led by Max Uhle first began excavations, which continued for several decades.

As for the Huacas, these are monuments from the pre-Columbian period in the Andes, often referred to as pyramids with tiered platforms. The word «huaca» also refers to places of religious rituals and is used to describe ritual vases found in burials. The Incas, who only emerged as a civilization in 1470, adopted all the positive achievements developed by the Moche: a complex urban layout, agricultural advancements with what we might now call genetic manipulation.

The Moche civilization did not have a written language; however, they mastered the art of creating astonishing ceramics—unmatched anywhere else in the world. These were sculptural depictions of people, animals, and plants. Some ceramics depict scenes of sacrifices, battles, and figures of deities. The faces portrayed on these artifacts are strikingly lifelike and expressive. For example, there is a depiction of a dead man playing the flute, with eyes made of mother-of-pearl and obsidian, or a potter in a turban making a grimace, and a small but intricately crafted black duck with a club and shield like those used by warriors. To these possibly ritual objects, one could add erotic vases depicting love scenes.

One ceramic vase portrays the wrinkled face of the god Ai Apaec, who is often depicted with fangs, a feature commonly associated with sculptures of Moche deities. A black figurine of a warrior with a peculiar helmet has raised more questions than it has answered, as this «warrior» resembles what modern-day «contactees» might depict as an extraterrestrial. In one burial site, a bottle was found in the shape of two small human figures, while another vessel with a handle is shaped like a «ceramic puma.» The significance of this vessel was quickly understood: the puma was considered a sacred animal by the Moche. The Moche, known for their aggressive tendencies, even depicted birds in a «military genre.» A vessel shaped like an ordinary duck is adorned with warrior attributes. Yet, these same artists glorified the immortality of warriors by depicting both a moose, a jaguar, and a snake on ritual vases.

In Moche mythology, reconstructed from vase paintings, two systems of time and space emerge.

One set of images illustrates episodes from myths, reflecting events that, in Moche thought, took place in the past. In these myths, zoomorphic deities act on Earth. The distinctions between them and humans are minimal, with the world of mythic pioneers almost replacing the human world. Animal-gods are opposed not by humans but by monsters. These monsters include everything from «Snark,» combining features of mollusks, predatory animals, and snakes, to the «Récuay Beast» with a snarling mouth at the end of its tail, muscular jaguar-like limbs, and the body of a reptile. There are also mythical fish, crabs, and turtles. An anthropomorphic demon, whose image suspiciously resembles that of two anthropomorphic deities, one of which defeats monsters while the other gives people cultural plants and oversees their ceremonies, also appears. Could the images of both the deities and the demon stem from a common prototype—the ancient master of animals? Such a figure was widespread among pre-agricultural tribes in America and Eurasia. With the advent of a new type of economy, this image transformed. In some cases, it became purely demonic, while in others, it evolved into depictions of deities. Among the Moche, the giver of plants was not only an agricultural god but also the leader of animal-like people.

Among the Moche monsters and demons, two groups can be distinguished. One (like the «Récuay Beast») clearly symbolizes chaotic forces. Their bodies seem to be composed of parts from different animals. Deities combat these forces, liberating the Earth. Others (mostly aquatic creatures like bonito fish, crabs, and shrimp) combine human traits with those of specific animals and, in this sense, are no different from zoomorphic deities. It seems that the world of these demons is structured like that of gods and humans because at least one demon performs the same rituals as humans. An anthropomorphic deity victoriously fights the sea’s inhabitants but does not seem to destroy them. Simplifying the overall picture, one could say that in their mythology, the Moche establish the ideal prototype of their culture (the world of gods), contrasting it with both «anti-culture» (the world of sea creatures organized like the divine one but hostile to it) and «non-culture» (the chaotic world of monsters).

Our deep dive into the «archaeological antiquities» of this region alternated with visits to beautiful beaches. The first of such beaches on this trip was Huanchaco Beach.

Located 13 km northwest of Trujillo, this sandy beach is famous for its unique boats. They are called «caballitos de totora,» which translates to «little reed horses» in English. These small, handcrafted vessels of the Moche culture were used by the locals to venture out to sea. The boats are entirely woven from totora reeds and have high, upward-curving bows. Riding such a boat initially requires some skill, but the locals race and fish on them with remarkable agility. Two fishing methods are practiced here: individual fishing with a hook and paired fishing with a net.

Cajamarca

During the height of the Moche civilization, their neighbors in the mountains were the creators of the Cajamarca and Recuay cultures. There are many depictions of battles between Moche warriors and people carrying bags for coca leaves, with trophy heads attached.

The road to Cajamarca winds through mountain slopes and gorges. In some places, the mountain road is so narrow that our bus had to either hug the cliffside or stop at the edge of a precipice to allow oncoming traffic to pass. As the costa (coast) transitions to the sierra (mountains), bare rocks initially dominate the landscape, creating a kingdom of stones. But after several hours of driving, the view opens up to an extraordinarily beautiful mountain valley. The lush green splendor seen from above has a quiet, captivating beauty. The city of Cajamarca itself is located at an altitude of 2,720 meters above sea level.

Cajamarca’s history traces back to pre-Inca times. The Cajamarca Valley was the center of the Caxamarca culture, which reached its peak development between 500 and 1000 AD. During the reign of Inca Pachacuti in 1465, these lands were annexed to the Empire of Tawantinsuyu (translated as the Four Regions of the World). During the Inca era, Cajamarca became an important administrative, military, and religious center. Temples and palaces were built here, the most notable being the so-called Cuarto del Rescate. On November 16, 1532, Cajamarca became the site of one of the most significant episodes in American history when a group of Spaniards, led by conquistador Francisco Pizarro, captured Inca Atahualpa.

Today, the city of Cajamarca has been recognized as a Historical and Cultural Heritage of the Americas and a Symbol of Latin American Unity—both titles awarded by the Organization of American States (OEA).

Additionally, this is the birthplace of Carlos Castaneda and Jorge González. This small city is nestled in a picturesque mountain valley with a thriving agricultural community. Just outside the city center, on rich pastures, you’ll find well-fed cows, sheep, llamas, pigs, geese, and other livestock. The locals are dressed in their traditional outfits and wear wide-brimmed straw hats. It was not uncommon to see groups of women in their straw hats and colorful skirts sitting on high green hills, engaged in their usual tasks: spinning wool, knitting, or weaving. They choose beautiful locations for their work as if the surrounding beauty provides inspiration and allows them to transfer that beauty to the items they craft. The secrets of spinning and weaving are passed down from generation to generation, from mother to daughter.

Nearby are the famous Banos de Inca (Inca Baths) or Baths of the Inca, known throughout Peru. The water temperature is a unique +70 degrees Celsius with special mineral properties. Inca Atahualpa was particularly fond of these natural baths. He would bathe here daily with his wives. Naturally, we couldn’t resist testing the effects of these mineral waters for ourselves. Moreover, Jorge González, upon learning that we were heading to Cajamarca, recommended that we visit them daily. After these wonderful baths, we would head to the massage salon located on the grounds of these thermal baths, where our revitalized and rejuvenated bodies were treated to even greater relaxation under the skilled hands of a local Peruvian masseuse (for some reason accompanied by gentle Japanese melodies playing from a portable tape recorder).

A few kilometers from the Inca Baths lies the agricultural estate known as «Ex Hacienda La Collpa.» The place is well-maintained, simple, and tasteful. There’s a pond with an island in the middle and a small house for geese and ducks, connected by a bridge. Nearby, horses graze peacefully. As you approach the cow farm, you pass through a beautifully kept yard that features a farm store. At the entrance to the yard, we saw two men in ponchos and wide-brimmed straw hats holding large drums. They beat a rhythm on their drums, inviting guests to a performance.

The performance surprised and delighted us. The main participants were about ten Collpa cows and two bulls. Each animal had its own name. The show took place as the animals returned from pasture to their stalls for feeding and milking. The herdsman, dressed in white and wearing the customary Cajamarca straw hat, cracked his long whip on the ground and called out: «Es-me-ral-da!!!» Soon after, the robust and stately Esmeralda appeared, swaying from side to side. She made her way to her stall, marked with a sign reading «Esmeralda,» guided by rhythmic drumming and the shouts of «Ava-a-nsa! Ava-a-nsa!!» («Keep moving! Keep moving!») from two farmers in ponchos and hats. Once inside her stall, she settled comfortably, waiting to be fed fresh grass and milked. The same process was repeated for all the other animals (Elena, Clarita, Taura, and other beauties), to our shared amusement and laughter. After the show, we took a closer look at the cows and then headed to the farm store. There, we tasted local cheeses, yogurts, milk creams, various types of honey, bee pollen, and other products. We bought the cheese we liked best.

We were also struck by another place called Cumbemayo, located 22 km southwest of Cajamarca in the San Pablo province, about an hour’s drive away. This site is said to have originated during the development of the Chavín culture. It holds an extraordinary mystical power and natural beauty. It’s also known as an ancient natural archaeological complex. The area features enormous stone formations, resembling a forest of rocks arranged in a mysterious order that can evoke altered states of consciousness. Local curanderos are said to perform White Magic rituals here. The atmosphere of this place is very conducive to meditation and contemplation. There is also an aqueduct from the pre-Inca period hidden in the rocks, along with a sanctuary adorned with petroglyphs and ceremonial altars (located within the aqueduct area).

In Cajamarca, there is another place where brujos (sorcerers) gather to perform communal rituals. We didn’t stay long there, merely passing by. In ancient pre-Incan times, the Casamarca people lived in this area. We were fascinated by their burial traditions. We visited one such cemetery called Ventanas de Otuzco (Otuzco Windows). On a high mountain, there are numerous window-like openings resembling large nests. When a person died, their body was dried using special herbs and potions. The lightened body was then carried to the mountain and placed in a pre-carved niche. Standing next to this rock, one can enjoy a breathtaking view of the Otuzco Valley, where the distant descendants of this remarkable people still live. They believe their ancestors reside where the sun rises, and indeed, every day the sun appears from behind this rock.

Thirty kilometers north of the city, in the picturesque village of Llacanora, lies the Granja Porcón estate, also known as the Atahualpa Jerusalem Cooperative.

To be continued…